When Talking About Social Determinants, Precision Matters

Public health experts have aptly expressed concern about the health care industry’s characterization of interventions as addressing “the social determinants of health” and have pointed out the limitations of over-medicalizing individuals’ social needs rather than investing in upstream community interventions. Acknowledging this concern and seeking greater internal consistency, the Health Care Transformation Task Force (the Task Force)—a coalition of payers, purchasers, providers, and patients committed to embracing value-based payment models—offers a framework to describe the distinction among social determinants of health, social risk factors, and social needs in a manner that promotes more precise usage of each term by all health care stakeholders. Clear and consistent terminology is an essential first step to determining what role health care providers and payers can and should play in addressing the underlying factors that influence population health. (Others have made similar points, notably Hugh Alderwick and Laura Gottlieb in The Milbank Quarterly.)

A Conceptual Framework For Health System Interventions

The term social determinants of health (SDOH) is ubiquitous in health care; equally pervasive is the misuse of the term to characterize health system interventions to address non-medical factors that contribute to health. Health care industry representatives often use SDOH interchangeably with other similar, yet distinct, health concepts, putting usage of the term in conflict with the way public health officials communicate about social determinants. The result is a disconnect in important conversations about how to improve health and reduce disparities. More than simply an issue of semantics, the lack of precision in terminology could negatively impact the health care industry’s ability to form strong cross-sector partnerships.

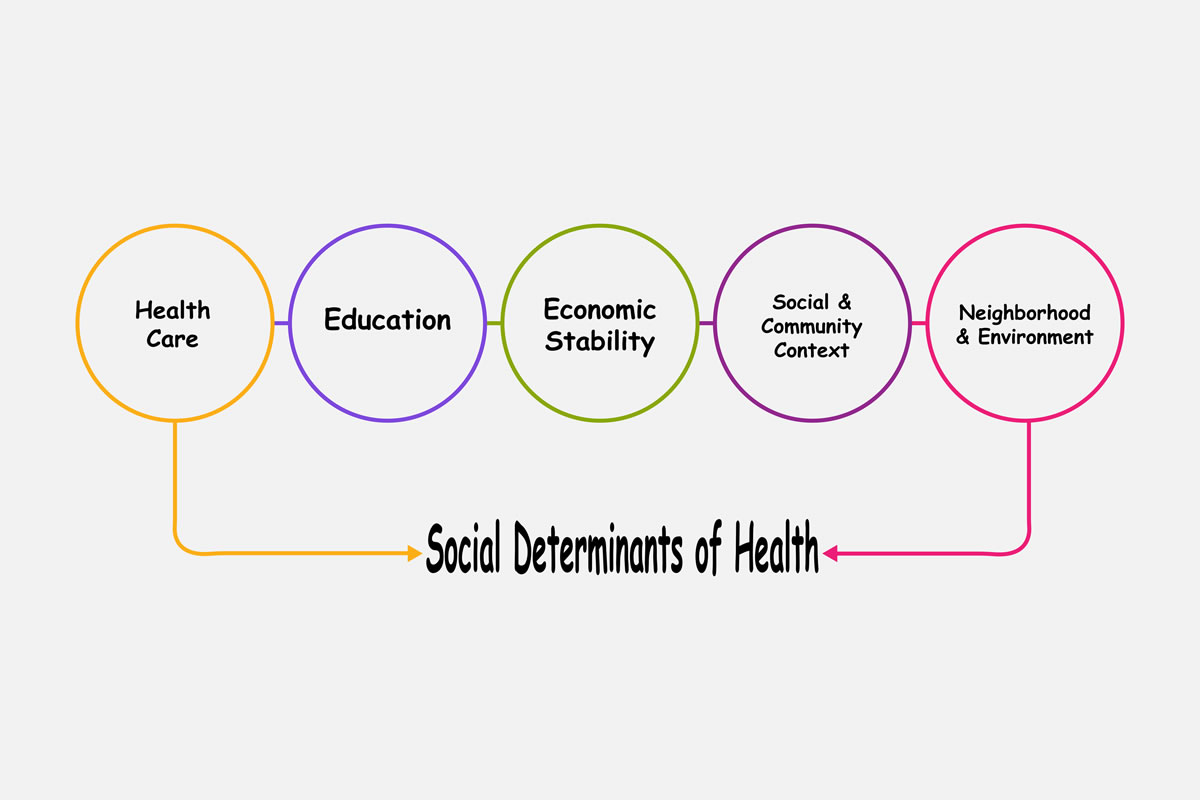

The concept of SDOH is not new; it has been a longstanding and central tenet of public health practice. Public health practitioners have referenced and consistently used the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of SDOH: the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life, including economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies, and political systems.

Building on the WHO definition, the Task Force has outlined five foundational principles that health care industry leaders should keep in mind when discussing and implementing interventions that address the non-medical factors that influence health:

SDOH Impact Everyone; They Are Not Something An Individual Can Have Or Not Have, And They Are Not Positive Or Negative

Too often, the SDOH concept is framed with a solely negative connotation. For the purposes of advancing health equity, it is essential to remember that there are social factors that confer health benefits to certain populations and cause harm in others. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Healthy People 2020 initiative identifies economic stability as one of five areas of SDOH. Just as economic stability can confer health benefits, economic instability can create health risks and challenges.

SDOH And Social Needs Are Two Different Concepts

Many industry-led efforts that claim to address SDOH aren’t actually addressing a community’s underlying social and economic conditions, but rather aim to mitigate the current social needs of individuals. As an example, an effort to provide fresh produce to people struggling to afford food mitigates an immediate individual need, but it does not address the underlying systemic issues that cause food insecurity. Imprecise use of the terminology could overstate the reach of the intervention.

Social Risk Factors And Social Needs Are Also Two Different Concepts

Social risk factors are defined as the adverse social conditions associated with poor health, such as food insecurity and housing instability. A person may have many social risk factors but fewer immediate social needs, which is why patient-centered care and engaging individuals in conversations about their unmet social needs are crucial to identifying which need is the most pressing for a patient in each moment.

Health Care Organizations Are Well-Positioned To Identify Social Risk Factors And Unmet Social Needs Of Individuals And Can Have An Important Role In Addressing And Mitigating These Needs

In a recent national survey commissioned by Kaiser Permanente, 80 percent of respondents said they would find it helpful for their providers to share information about community resources, help them apply for specific resources, and follow up if they or a family member were in need.

For System-Level Solutions To Address SDOH, We Need To Move Beyond Silos

There is a growing recognition that truly improving the health of our nation requires partnership and breaking down silos among health care, public health, and social services, as no single entity is able to tackle the upstream social conditions on its own. Traditionally, these entities have operated with distinct and separate missions: Public health has been responsible for population health and disease control, the health care sector has provided clinical care, and social service agencies have addressed access to the resources and services necessary for healthy living (for example, housing, education, and transportation). Our nation’s growing health care costs and poor outcomes, including a maternal mortality and morbidity crisis, are evidence that this siloed approach isn’t working.

Why Does Precision Matter?

Many current and proposed policy initiatives provide opportunities to address SDOH and social needs in communities across the country. To do so effectively, health care industry and public health leaders need to agree on common principles to guide their activities. Using precise terminology will help enable partnerships between public health and industry to address the full continuum of SDOH, social risk factors, and social needs to advance health improvement and equity.

As shown in Exhibit 1, addressing SDOH can be categorized as an upstream, communitywide intervention to address the root causes and conditions (for example, economic instability) that contribute to poor health, whereas addressing social risk factors and social needs are midstream approaches to mitigate an individual’s adverse conditions and unmet needs (for example, food and housing).

Exhibit 1: Examples of interventions across the continuum of SDOH, social risk factors, and social needs

Source: Authors’ analysis of interventions.

Leveraging The Strengths Of Cross-Sector Partners

One example of an upstream intervention to address SDOH is ongoing advocacy by Atrius Health, an innovative nonprofit health care leader serving Eastern Massachusetts. Atrius Health is promoting legislation that would allow low-income populations to apply for MassHealth, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and state-administered safety-net programs through one common application. Atrius Health is leveraging its political capital and industry voice to seek systemic changes that address the economic stability of its patient population and that of low-income Massachusetts residents at large.

In an effort to address social risk factors and needs, the Route 66 Consortium (the accountable health community in Tulsa, Oklahoma) is screening individuals in five areas that contribute to poor health: housing insecurity and quality, food insecurity, unmet needs for utility assistance, interpersonal violence, and unmet transportation needs. The Route 66 Consortium is a cross-sector partnership including the county health departments in Tulsa and Oklahoma City, Oklahoma’s nonprofit health information exchange, local social service agencies; and health care providers such as federally qualified health centers. Based on the screening results, health department navigators connect people to community resources that provide assistance (for example, food banks, utility assistance programs). The program, which has connected more than 2,000 people with resources since 2017 and was recently expanded statewide, is an outstanding example of how partnerships among the health care industry, public health, and community-based organizations can leverage each sector’s strengths and resources to improve individuals’ health and well-being.

Opportunities For Innovation On A National Scale

Amid ongoing multisector work at the state and local levels, innovation at the federal level can help pave the way for cross-sector efforts to address SDOH, social risk factors, and social needs on a national scale. Starting in 2020, Medicare Advantage (MA) plans will have greater flexibility to offer chronically ill beneficiaries non-medical benefits (for example, transportation, healthy food options, and home improvements). This policy change presents the health care industry with a new opportunity to address MA enrollees’ social needs. In addition, the expanded flexibility could encourage health plans to partner with community-based organizations and invest in areas where there are gaps in meeting social needs.

The recently introduced Social Determinants Accelerator Act of 2019 would convene a federal inter-agency technical advisory council to identify opportunities for state and local governments to coordinate funding and administration of federal programs that may be underutilized or unknown. The act would also provide grant funding at the state, local, and tribal level to fund social determinants accelerator plans that would catalyze greater community partnerships and uptake of evidence-based interventions to improve health outcomes. These plans would target groups of high-need Medicaid patients (for example, homeless individuals, mothers with post-partum depression, nursing home residents); they would also include a strategy for enabling data access across programs to measure impact and return on investment.

As new policy ideas and programs move from the proposal to implementation stage, precise usage of the terms above by all stakeholders will be critical to ensure common understanding of the scope of each intervention and identify additional opportunities for engagement across the continuum of SDOH, social risk factors, and social needs.

Next Steps

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s recent multi-million dollar funding opportunity and call for proposals, “Health Care’s Role in Meeting Patients’ Needs,” is evidence of the growing interest in and need for greater clarity in identifying critical contributions that the health care industry can make to address SDOH, social risk factors, and social needs. As stakeholders grapple with the question of what role the health care industry can and should play in addressing SDOH and social needs, there are other key components necessary to make partnerships work. Sustainable infrastructure and shared financing are vital to develop and maintain long-lasting, fruitful cross-sector partnerships. One-time investments (for example, pilot funding) are helpful in launching partnerships but often are not sufficient to make a sustainable impact on communities.

As the transition to value-based payment continues and providers take on greater risk to improve health outcomes, addressing the upstream causes of poor health will continue to be essential. In fact, recent research from the Journal of the American Medical Association shows physician practices participating in bundled payments, primary care improvement models (for example, medical homes), or a commercial accountable care organization had higher rates of screening for five key unmet social needs (housing instability, food insecurity, utility needs, transportation needs, and interpersonal violence) than physicians not participating in value-based arrangements. The framework presented above highlights the various upstream and midstream levels at which the health care industry can effectively engage. Task Force members and like-minded organizations will continue to work with public health and community organizations to identify the appropriate role of the health care industry beyond direct service delivery to promote community wellness. Each stakeholder has an important role to play in what should be a harmonious collaboration. Precise use of terminology is an important first step in determining what those roles should be.

Credits: Katie Green and Megan Zook (published on October 29, 2019 - Health Affairs)